'The Question of Social Impact Challenges Science'

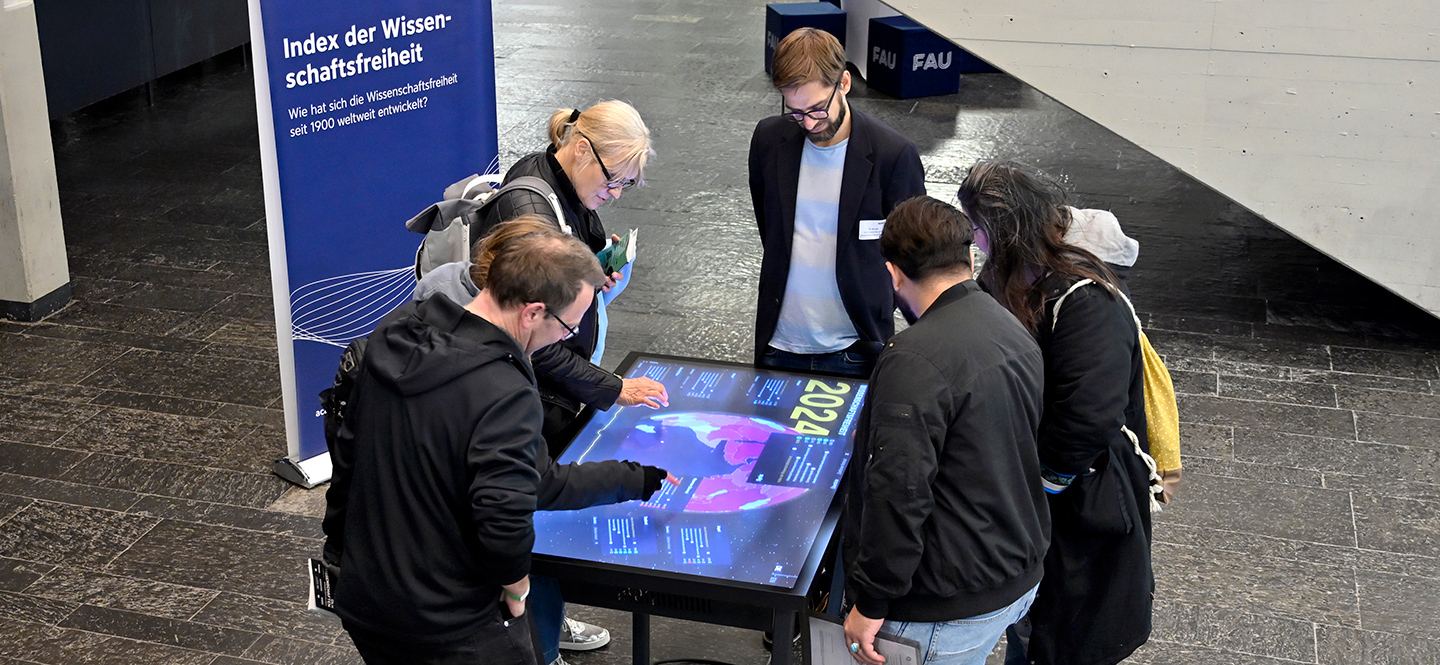

FAU/Harald Sippel

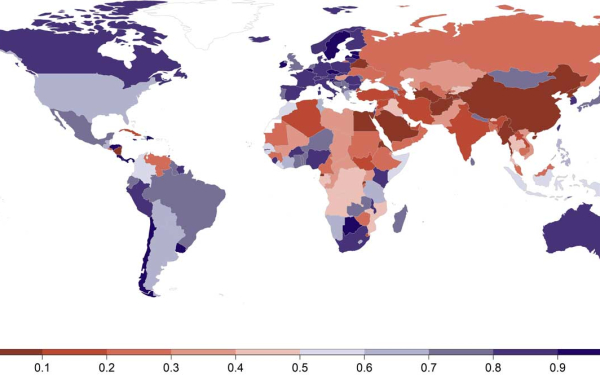

The interactive globe of academic freedom shows the academic freedom index for all countries in the world with a comparison over time since 1900.

Every day, Katrin Kinzelbach and Lars Lott could stand in a lecture hall explaining the Academic Freedom Index. Demand is high. So is the burden on the researchers. How can a balance be struck between science and impact?

More than 2,300 country experts provide the data for the Academic Freedom Index (AFI). In just a few years, the AFI has become a highly regarded indicator of academic freedom in almost 180 countries. A conversation with Katrin Kinzelbach, one of the initiators of the AFI, and Lars Lott, the project coordinator, about the tension between science and – political – impact.

How did you come up with the topic?

Kinzelbach: In 2017, I was a visiting professor at the Central European University in Budapest, which was under considerable political pressure at the time. A year earlier, researchers had to flee Turkey to avoid ending up in prison. These events reinforced my impression that academic freedom was under threat. I then asked myself: what empirical evidence is there for this thesis? And I realised that the data available was insufficient. That's how the crazy idea of developing an index that compares academic freedom internationally came about.

Against the backdrop of the reputation economy surrounding the various university rankings, we first thought of collecting data for individual institutions and adding the important dimension of academic freedom to the rankings. But we decided against this, firstly because it would have completely overwhelmed us in terms of data collection, and secondly because a colleague from Syria convinced me with a counterargument: even in highly repressive contexts, there are universities that manage to achieve a certain degree of academic freedom. Highlighting these in particular could provoke repressive regimes even more. So we focused on the country level.

Katrin Kinzelbach has been a professor at FAU since 2019 and holds the Chair of Human Rights Policy. Before moving to FAU, she was deputy director of the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin.

What political impact has the Academic Freedom Index had so far?

Lott: We provide information to decision-makers on request, whether at EU, federal or state level. In the German Bundestag's research committee, for example, we explained to members of parliament how the Academic Freedom Index works and how it can be applied in politics. But I can't say for sure what impact this will ultimately have. At least governments seem to care about how their countries are rated. We received a complaint from a ministry in Mexico because Mexico was given a lower rating with each annual recalculation. They said that the expert assessments must be based on incorrect data and that we should correct the assessments. This episode shows that the AFI is noticed by governments and has developed a certain reputation logic.

Kinzelbach: Since we have created a scientifically sound instrument with the AFI, we receive a wide variety of enquiries in the current world situation. Our focus is always on explaining the methodology first and classifying the data. This is because sometimes people read something into the data that is not actually there.

The Academic Freedom Index provides initial guidance, especially for countries that are not in the media spotlight on a daily basis.

Of course, we are also often asked what we suggest to protect academic freedom. Then we have to leave our role as researchers and move into policy advice. In doing so, we always make it clear what we offer as guidance based on our own expertise and what we can actually prove with the data – or indeed what we cannot prove. We cannot offer simple, ready-made solutions. But through our research, we have identified determinants of why academic freedom is well protected in some contexts and declining in others.

Lott: In addition to requests from politicians, institutions also want advice on how to minimise risks when cooperating with difficult partner countries. We also know that the index is consulted when funding decisions are made to support researchers who are under threat. Everyone knows what the situation is like with regard to academic freedom in China, the USA or India, but the Academic Freedom Index provides initial guidance, especially for countries that are not in the media spotlight on a daily basis.

What recommendations do you make to minimise cooperation risks?

Kinzelbach: The index should not be used as a tool to rule out scientific cooperation from the outset. Recently, for example, we were asked what the expansion of the Horizon Europe research programme to Egypt, which scores very poorly in the index, means. However, a poor ranking in the AFI does not necessarily mean that a country is a no-go zone for cooperation.

Lars Lott has been a research assistant at the Institute of Political Science at FAU since 2022. He is the project coordinator for the joint research project with the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem) at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden on the AFI.

A poor ranking in the AFI does not necessarily mean that a country is a no-go zone for cooperation.

If academic freedom is significantly restricted, and this affects not only individuals but also institutions, then the first step should be to discuss whether cooperation at the institutional level is even desirable. Or are the institutions in the country perhaps already so tightly controlled that there is a risk of being instrumentalised by highly repressive regimes?

When we talk about individual cooperation, in projects or in personal exchanges, then we have a completely different debate. In this respect, I would not make any sweeping statements, except that a poor performance on the Academic Freedom Index should not lead to the cessation of scientific cooperation.

What further impact would you like to see from the Academic Freedom Index?

Kinzelbach: I would like to respond with a brief digression on the subject of 'impact'. Our project is one that can be used as an example to discuss this. We are pleased about the growing visibility in non-scientific circles, but we have to balance our public engagement with the time budget for our own research.

The question of how the project benefits society challenges the inherent logic of science and requires us researchers to explain ourselves in non-scientific terms. This is a contentious issue that has implications for academic freedom. What non-genuinely scientific aspects should researchers take into account when organising their work and selecting their fields of research?

Lott: Our primary task is to work with the data and produce scientific results. Only then does the question arise of how we can use the results to influence society. The data does not speak for itself, but must be contextualised so that it can inform social debates and thus have an impact.

Kinzelbach: A research project can only have a truly reliable impact if it has a solid research concept and its methodology meets scientific standards. The solid foundation of the AFI certainly contributes to the fact that we are now recognised internationally.

I recently received a call from the New York Times. For a moment, I thought, wow! We have also been asked by colleagues in the USA whether we could advise them on what data on academic freedom in the USA should now be collected. We would be very pleased if our project had a certain influence in the debate on attacks on academic freedom in the USA. But it is also clear that an index cannot save academic freedom. We can only use comparisons to show how it is developing worldwide.