Jakob Schnetz für VolkswagenStiftung

Every year, hundreds of thousands of latex mattresses end up in the bulky waste in Germany. They are incinerated because there is no recycling process for them. The REFOAM research project aims to change this.

The fairy tale princess on the pea would be impressed – but probably a little disgusted. Here, inside a concrete warehouse in Erftstadt, you can find hundreds, perhaps thousands of piled up mattresses. But where in the fairy tale there is a pea at the bottom, here only a stray cat runs across the top of the mountain of mattresses. This is because these mattresses come from discarded bulky waste, collected and sorted out with a grab excavator by the waste disposal company Remondis.

Based on sales figures and the lifespan of the products its members produce, the German Mattress Industry Association estimates that in Germany alone people throw away some 1.5 million mattresses every year. An analysis commissioned by the German Environment Agency in 2020 even calculated that 225,000 tons ended up as bulky waste in Germany in 2017, which corresponds to six to eight million mattresses. By any measure, that's a lot of waste – or is it possibly not waste at all?

Low material utilisation of mattresses to date

Currently, around 45 per cent of all mattresses disposed of in the European Union end up in landfill sites, while 35 per cent are thermally recovered, i.e. incinerated to generate energy. Material recycling is the exception rather than the rule, although Remondis does remove the metal from innerspring mattresses and sells it to scrap dealers. A small number of polyurethane mattresses are downcycled for further use in the production of insulation material. However, pocket spring mattresses and those with memory foam toppers end up being incinerated for technical reasons: the different materials cannot be separated – this would require a recycling-optimised product design. For discarded latex mattresses – around ten per cent of total production – there is so far no feasible concept for reusing the plastic.

The waste disposal company Remondis collects and sorts the mattress waste from an area, where appr. 800,000 people live.

This is where another location comes into play that could hardly be more different from the waste disposal centre in Erftstadt. It is the historical building that houses the geosciences at RWTH Aachen University, the second oldest building of the university, which was founded in 1870. Two imposing sandstone pillars support the portal of the main entrance. Inside, it looks a bit like an installation by artist Christo Javacheff – everything is shrouded in white, as the university is currently having the building refurbished.

The goal: chemical recycling for latex mattresses

So it is that Fabian Roemer leads us through old laboratories with red floor tiles and outdated-looking fume cupboards, but also uses a cosy and modern meeting room to present an idea: the REFOAM project. Roemer conducts research at RWTH Aachen University in the field of Thermal processes and emission minimisation in the waste disposal and recycling industry.

Fabian Roemer is a doctoral student in the team of REFOAM project leader Prof. Dr. Peter Quicker at RWTH Aachen University.

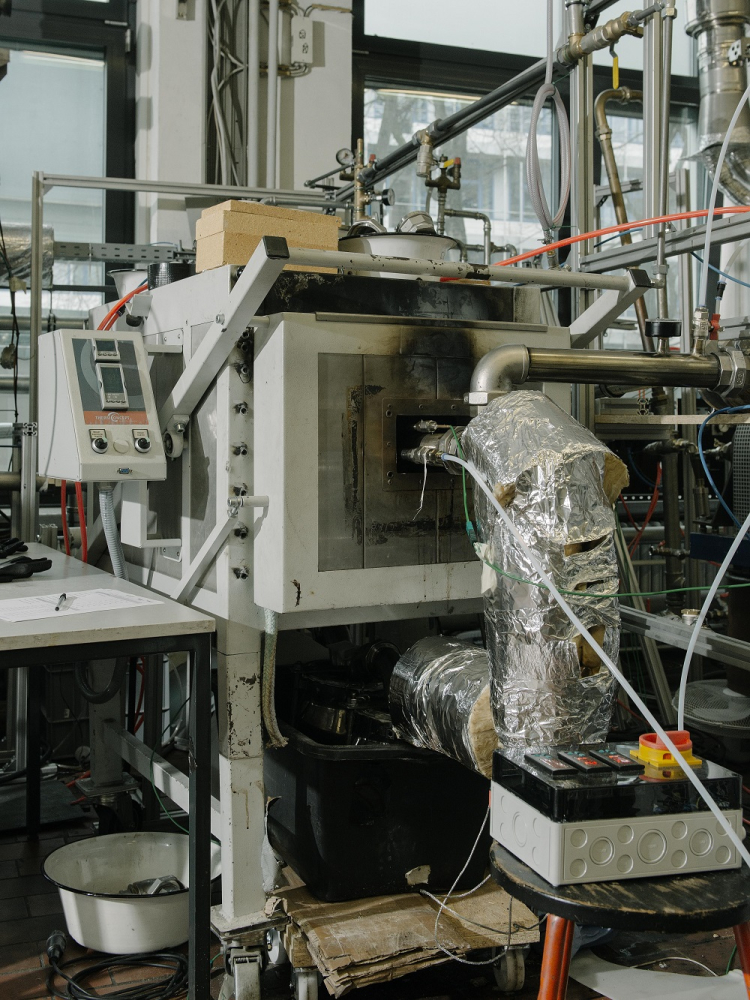

14 non-teaching staff and 21 research assistants from the fields of mechanical engineering, engineering, chemistry and biotechnology work here. Together with senior engineer Dr. Kevin Carl – the right-hand man of Institute Director Peter Quicker – and other partners inside and outside the university, Roemer, as an expert in chemical recycling, intends to investigate whether there might be better solutions at the end-of-the life cycle of latex mattresses than incinerating them. With well-equipped laboratories and an exceptional technical centre, the institute offers all the necessary research and development facilities for this task.

"We are a group of idealists," says Carl, describing the working group, "we are interested in working with companies to bring sustainable solutions to the market and achieve a real ecological impact". Carl sees two important reasons for recycling latex mattresses: those made from synthetic latex are based on petroleum. For mattresses made from natural latex, on the other hand, the biogenic material obtained from rubber plants is scarce and therefore categorised as a critical raw material. The more latex can be recycled, the less latex has to be produced from climate-damaging crude oil or the limited amount of rubber plants available. Additionally, less CO2 is released.

Lead engineer Dr. Kevin Carl sees two important reasons for recycling latex mattresses.

Difficult sorting of mattress waste

The first challenge for recycling already comes at the very beginning: Remondis is currently sorting the latex mattresses out of the present mountain of mattresses by hand. The researchers in Aachen want to develop a sensor-based sorting system that can be used on an assembly line. Over the course of the project, a pilot plant is to be built in Erftstadt that will automatically sort "significant quantities" of mattresses. The Aachen researchers can build on the previous experience of the Chair of Anthropogenic Material Cycles in sorting plastics from the so-called "yellow bag" used by German households to separate plastic packaging waste. The reseachers in the group around senior engineer Dr. Alexander Feil use near-infrared sensors that use reflection to distinguish whether a mattress is made of PU foam, latex, or another material. When the mid-infrared spectrum is added, the sensor can even detect the age of a mattress and secondary components such as flame retardants. This is made possible by sophisticated mechanical pre-treatment and AI-supported pattern recognition. "With our mattress samples from production waste, this works well," reports Carl from preliminary experiments.

The task of training the AI-model on heavily soiled mattresses from bulky waste, though, makes him more sceptical. Dirt from other rubbish, sweat and other bodily fluids or even bedbugs make automatic analysis difficult. "Incidentally, the latter are one of the reasons why the latex mattresses are not mechanically recycled – the little bugs can survive this," explains Carl. Another reason are the softeners used in the production of old mattresses: With mechanical recycling, they would remain in the cycle. It is possible, though, to destroy them thermally.

Pyrolysing the latex for raw material recovery

Once the latex mattresses have been sorted, the project plan envisages pelletising them so that they can be transported more easily via screw conveyors. The plastic is heated and pressed viscously through a rotating disc. This compresses the originally very airy material and presses it into small pieces. The researchers then want to pyrolyse the pellets, i.e. heat them to several hundred degrees in the absence of oxygen. This produces a solid residue as well as gas and a condensate, a yellowish or brownish oil depending on the temperature.

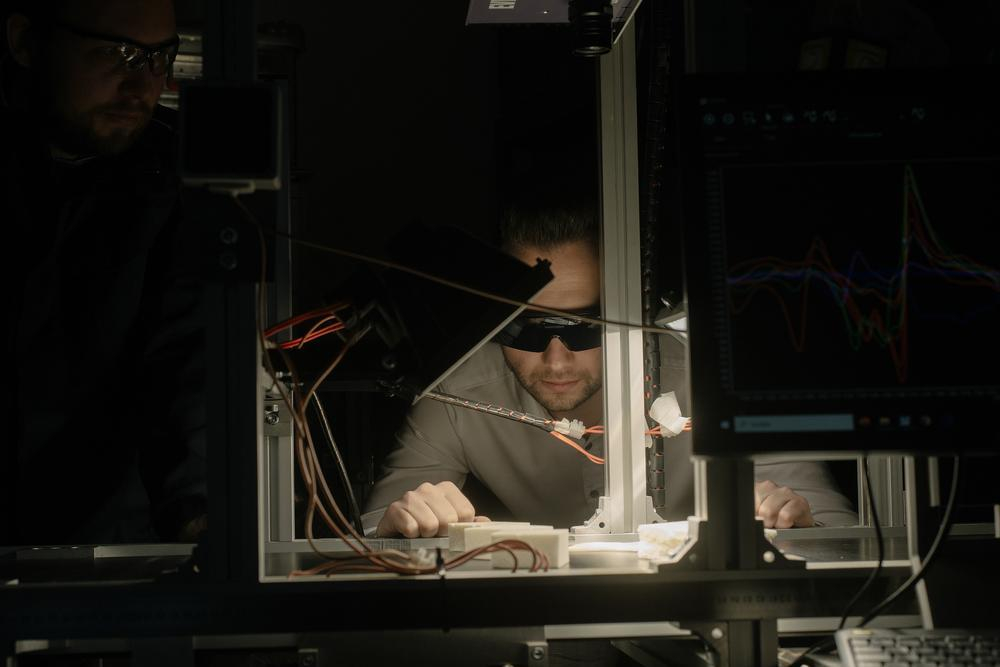

Kevin Carl (right) and his colleague Fabian Roemer (left) examine a sample of the oil fraction produced by pyrolysis.

According to preliminary tests, the residue known as "pyrolysis coke" accounts for around ten per cent by mass. It contains zinc as a valuable material that can be recovered. The gas consisting of nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and smaller hydrocarbons can be burnt to generate energy and used directly to heat the pyrolysis process.

75 per cent of the mattress can be used like petroleum

Interestingly, the oil can make up to around 75 per cent of the mass of the original mattress depending on the process conditions As pyrolysis breaks the originally long molecular chains into very different lengths, the oil contains well over a thousand different compounds. One task of the project is to find out what these are, in what quantities they are formed and at what temperature. To do this, the researchers use small sample quantities, which they place in ceramic crucibles on a thermobalance. This allows them to measure the amount of weight lost at different temperatures, while an infrared gas analyser records which substances pass into the gas phase. "We need a mass and elemental balance of condensate, coke and gas so that we know what we need to do for scaling," explains Roemer. How quickly should a temperature be reached and how long should it be maintained in order to produce the optimum product and few pollutants?

We are interested in working with companies to bring sustainable solutions to the market and achieve a real ecological impact.

It is already known that excessively high temperatures lead to the decomposition of fluorine salts and the formation of problematic fluorocarbons. At even higher temperatures, zinc sublimates and ends up in the oil – which could then self-ignite. On the other hand, it could make sense to remove sulphur early on in the process, because if it ends up in the oil, it corrodes metals and could cause problems with car catalytic converters or discolour plastics in their synthesis, for example.

In the large factory hall at RWTH Aachen University, the table football is of course a must.

In the long term, it would be conceivable to separate sufficiently highly concentrated valuable substances directly from the oil. Initially, however, the pyrolysis oil would be added to crude oil and co-processed in established refinery processes. "If we add 20 per cent pyrolysis oil to the mix, we are replacing 20 per cent crude oil," says Carl. "Everyone in the industry wants sustainable alternatives to crude oil, but there isn't that much on offer," says the lead engineer.

Numerous practical challenges

Carl sees an exciting challenge in bringing together two very different worlds: "When recyclers talk about impurities, they are thinking in terms of percentages. In processes quite commonplace in chemicals production, however, values in the permille range are already disturbing."

The raw material petroleum usually has comparable properties. "But waste can contain anything, and there are also seasonal and local fluctuations in composition," says Carl.

However, even if a process can be developed over the next four years that covers everything from sorting to extracting the pyrolysis oil, it would be no guarantee of success. "The process has to be economical," says Roemer. "The better we develop the process, the greater the added value, and therefore the greater the willingness of companies to invest in the necessary equipment."

At project partner Remondis, the mattresses have to be broken down into their components by hand. The AI-based classification of the material should make sorting technically possible in the future.

How ecological is material recycling?

And the process has to overcome one last hurdle: "It is very important for us to carry out a life cycle analysis at the end of the project," emphasises Carl: "Is what we are developing really better than continuing to produce polymers from crude oil, burning old mattresses and capturing the CO2 emissions in the process in order to use the gas as a raw material?" The project must be measured against this. "We already had one case where we turned one pollutant fraction into three through a recycling process," recalls the senior engineer. "Incineration made more ecological sense."